By Jordan Stone, MS4

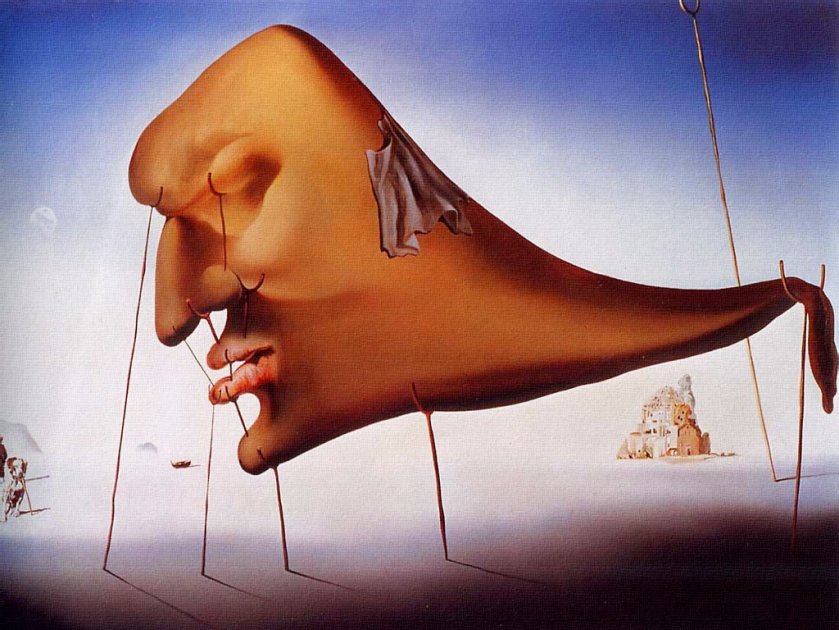

Background: During medical school, many students conduct clinical research studies involving human subjects. These projects often emerge from powerful visions of a better way to deliver care, and each vision is itself an engine propelling the unemotional, tedious labor performed in its service. Done assiduously, the day-to-day work draws out a familiar pattern of symptoms. To spend prolonged periods turning medical records into workable data, for example, entails pain behind the eyes, a headache encircling the forehead, a bridge of ache across the wrists, progressively poorer posture, and, if one is not judicious, a Spotify “Discover Weekly” dominated by “research music” (this is perhaps the most enduring of the symptoms described). In this author’s experience, the young clinical researcher develops two identities. One is the objective, dispassionate repeater of tasks; the other, the passionate, emotional humanist glimpsing the forest beyond the trees. Much has been written about the latter. Less is recorded, however, on the emotional dimensions of day-to-day clinical research.

Purpose: To explore how it feels to be a young medical student conducting clinical research about very sick patients in challenging clinical and life circumstances.

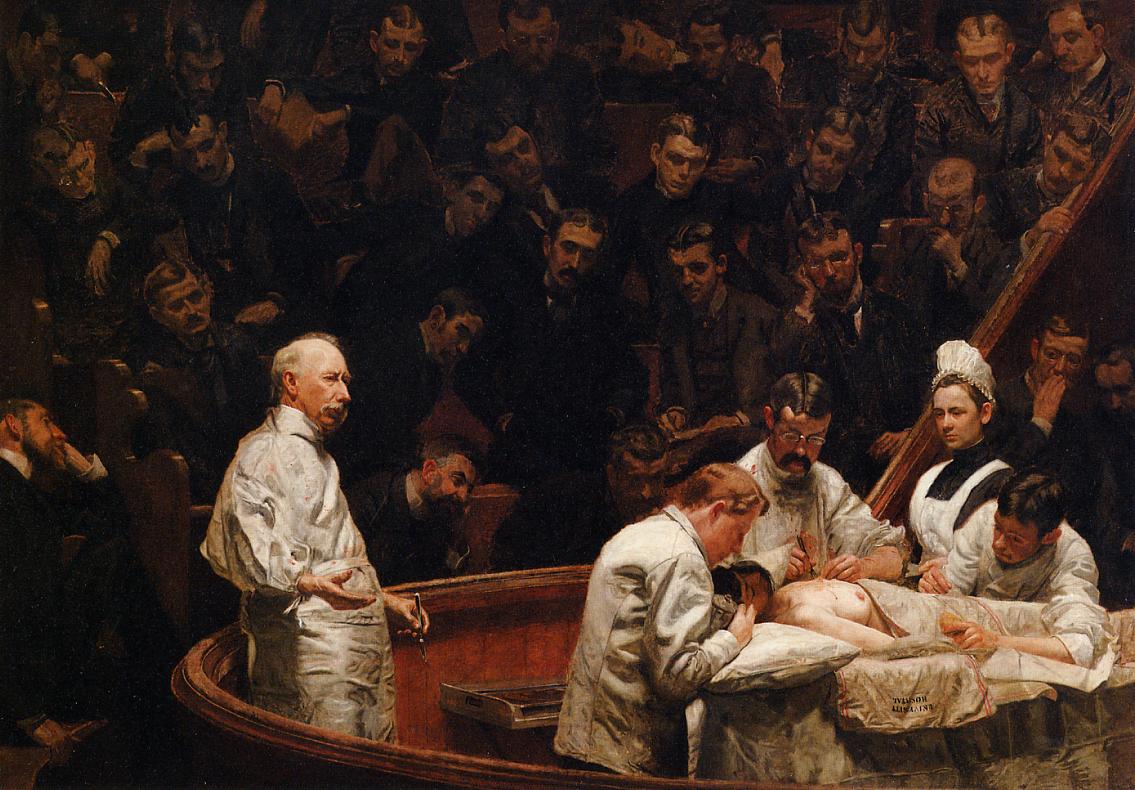

Methods: Review the charts of 250 patients diagnosed with gynecologic cancers, that is, cancers of the uterus, ovaries, and other organs along the reproductive tract. Note that these patients’ tumors all underwent molecular profiling, where the tumor is analyzed for meaningful changes in the tumor DNA. These changes enable the tumor to grow like a wild vine or to invade far-flung corners of the body. They are also targets for new drugs, and that is the true purpose of the molecular profile, to match new drugs to critical DNA changes.

Start with bread and butter data gathering — name, date of birth, sex, insurance coverage. All in the medical record, all neatly templated on the same page. Reflexively click on this page as soon as the patient’s chart opens. Document race; wonder what to do when it’s documented as “Other”; ponder the disappointing lack of specificity in amalgams like “Asian/Pacific Islander”, or “White, Non-Hispanic”. Smirk when you find a 70-year old patient who shares your birthday.

Open the chart of a deceased patient—a pop-up message asks if you are sure you want to open the chart of this patient, as they are deceased. Notice the background color of this patient’s chart interface is a much lighter shade of gray than charts of the living. Document the patient’s birthday, feel a pit form when you type the year, “1987”. Take off your headphones, go to the bathroom, wash your hands, come back, put your headphones on, click hurriedly through her chart. Open a new patient. Piece together from years of clinic notes the number of distinct chemotherapeutics she’s received. Balk when you arrive at 12. Recount them—13, actually. Gloss over the side effects: “nausea refractory to several medications”, “profound fatigue”, “depressed about hair loss”. You do not have a column in your spreadsheet for these—no sense in reviewing them. Catch yourself reading about a patient admitted 8 times in 4 weeks for obstructed bowels. Recall, with shame, that the 2.5 days you spent in the hospital for appendicitis felt like an eternity. Silently thank an OBGYN resident for documenting all of another patient’s discreet chemotherapy cycles in a single line of clinic note text.

Marvel at your own efficiency—now, you can parse 10 paragraphs of a GYN Oncology clinic note to fill 5 spreadsheet cells in under 2 minutes. Initially read notes from Social Workers, Palliative Care, Hospice, then begin to filter them out when they prove hollow for the purposes of your work. As time wears on, notice yourself disconnecting from the patient’s narrative altogether as you process each chart down to bones and repackage it into neat spreadsheet rows.

Find the molecular profile report for each patient—some have undergone the process several times, you learn. Note when the report was issued, where in the body the tumor sample came from. Copy down the alphabet soup of DNA changes identified, the list of suggested experimental drugs printed in a box along the bottom like lottery numbers. Read the appended pages of text about each drug; realize their contents are unimportant to the experiment and stop reading them altogether for subsequent patients.

Develop a way of entering the alphabet soup and the drugs into Excel so they are easy to analyze. Reward this absolutely brilliant idea—to separate each DNA change or drug name in its own cell instead of clumping them together— with a handful of trail mix. Sigh with relief and eat another handful of trail mix when you come across a report with only one or two DNA changes to transcribe into Excel. Visualize a graph charting the inverse relationship between number of DNA changes and ease of transcribing the report into Excel. Tuck your knees to your chest and ponder over another handful of trail max: many of these reports have only one or two DNA changes, zero or one experimental drugs recommended. Attempt to fathom the pits formed in the stomachs of patients receiving this news: we found no actionable DNA changes; no new drugs targeting your mutation; no highlighted clinical trials in the report. Reach into the bag of trail mix, feel around the empty bottom, take your headphones off, go to the bathroom, wash your hands again.

Results:

Sample Documentation from Patient Charts:

“…Though molecular profile suggests the patient may respond to this drug, the patient’s insurance denied coverage for the drug. Called insurance company last month per patient’s request and submitted formal appeal. Insurance company sent denial letter this week. Patient is devastated, is asking about costs of drug out of pocket. Patient given out-of-pocket estimate, requests information regarding additional financial aid. Patient to return to clinic next week to discuss options.”

“…Patient discontinued drug due to intolerable side effects.”

“…Discussed with patient absence of curative options at this juncture. After lengthy discussion, patient elects hospice.”

“…Patient reports she is hopeful, as she is a potential candidate for clinical trial”

“..Patient reports relief in hearing from clinical trial coordinator this week, continues to be hopeful about the trial’s potential. Return to clinic in one week.”

“…Patient without clinical or radiographic evidence of cancer following recent treatment with Drug A, no further treatment recommended at this time, return to clinic in 1 month.”

“…Patient’s daughter says she would like to take her mother home from the hospital for her 70th birthday. Inquires whether mother can eat a small slice of favorite cake in context of recurrent bowel obstructions. Risks and benefits discussed.”

Discussion: Recently, I sat down with a gynecologic oncologist during a residency interview, and we got to talking about the potential of these molecular profiles in women’s cancer care.

“Sure, molecular profiling opens up the door for a more personalized, targeted way to treat women’s cancers.” She folded her hands on the table and twisted her body toward the bookshelf. “But it can also offer patients false hope.”

She offered an example of a patient under her care, who underwent profiling of an advanced ovarian tumor. The profile turned up a dozen actionable mutations, and a drug tailored to one of the DNA changes in the report. .

“It was a lifeline for the patient. Really. She was ready for battle in my office that day. I recommended we start the new treatment quickly, assuming her insurance company covered it. A week later, the insurance company denied coverage for the treatment citing lack of evidence that it would provide appreciable benefit.” I thought back to the walls of appended drug text I’d skipped over in the reports—‘unimportant to the experiment’.

And what about paying for the drug out of pocket?

“Would have bankrupted her.” Without the negotiating power of a large insurance company, patients paying out-of-pocket often bear the “sticker price” for a drug—that is, the price before any negotiated discount is applied. For new drugs, the cost to the patient could be financially ruinous.

“So the ethics are gray here. Is it right to stoke a cancer patient’s hopes with advanced diagnostic tools and the promise of better treatments, when we know we could fall short of delivering? When we know the insurance companies are reticent to give the green light?”

How about clinical trials? Those often bypass insurance companies altogether, and the molecular profiles highlight several potential trials tailored to a patient’s results.

“That’s another challenging issue, because clinical trials for women’s cancers are horribly underfunded.” To her point, funding for Phase 3 clinical trials—the last hurdle companies must jump to demonstrate that drugs are safe, effective, and at least no worse than what is already on the market—has plummeted for gynecologic cancer drugs since 2010.

“That’s what keeps me up at night—the knowledge that what stands in the way of my patients receiving the best care possible comes down to insufficient funding, not insufficient knowledge or clinical capability.”

We heard a knock on the door just then, signaling the end of the interview.

Conclusion: Research is meant to be an objective undertaking, strongest when the emotional biases of the researcher are tamped down to a minimum. This says nothing of the emotional experience young researchers may face in engaging with saddening, frustrating, or even traumatic subject matter. Predominantly, it is the heady process of developing a big research idea that draws on humanistic qualities like empathy or compassion for sustenance. But, the day-to-day mechanics of research should not be discounted in their potential to draw from young researchers a spring of emotional engagement with those subjects that make us most human. More research is required to depict the full scope of this experience.